2020

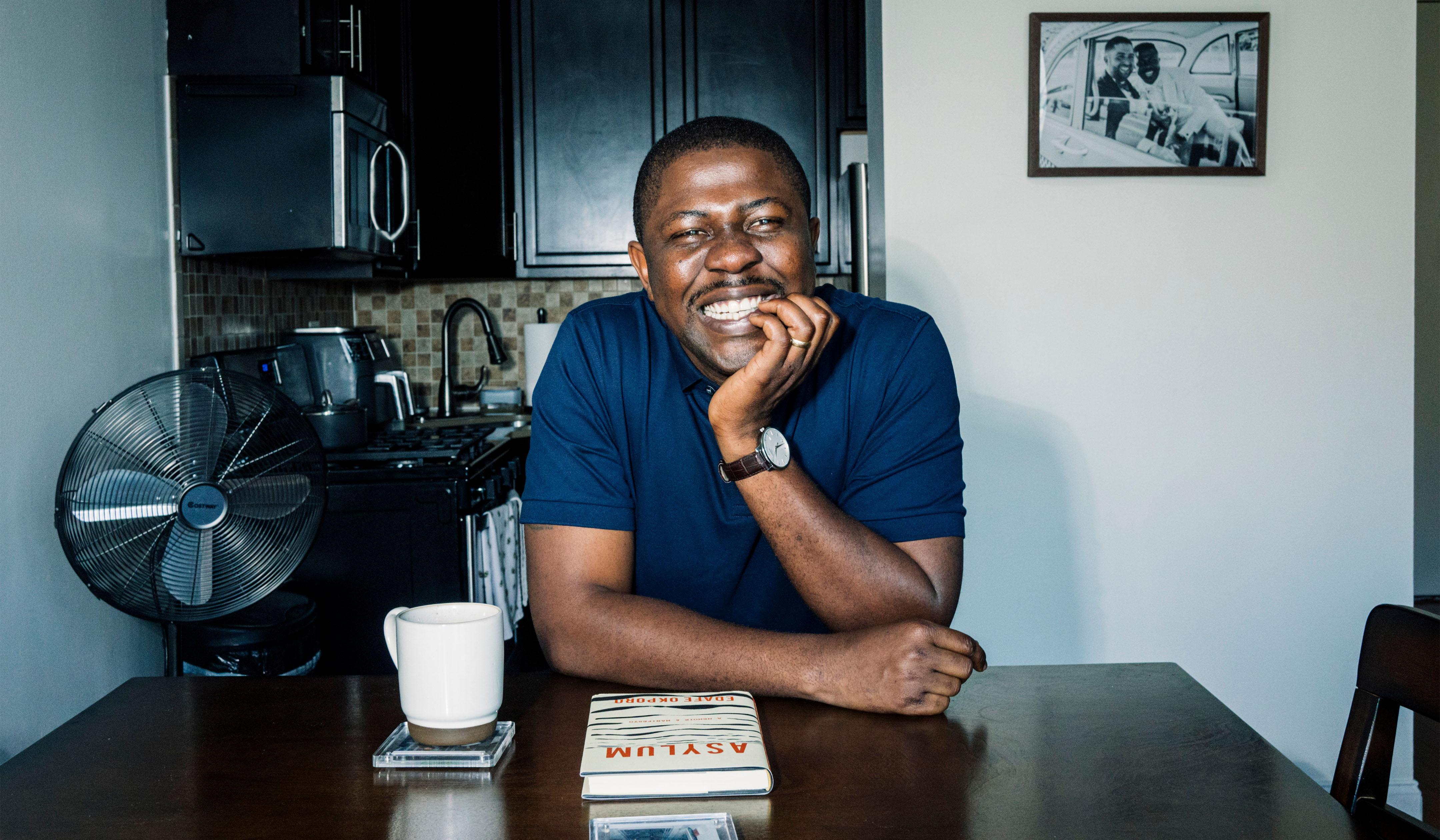

Edafe

Okporo

Edafe Okporo has a complicated relationship with the idea of home. For the first 26 years of his life, Nigeria was home. It was where he was born, grew up, studied, started to build his adult life. But to a gay man in a time of political scapegoating of the country’s LGBTQ community, his country felt more like a battlezone.

“Home is wherever you feel safe,” he reflects on his journey to New York City. “I knew I had to create a home here because in Nigeria, there was no longer a sense of home.”

When he was 12 years old, Edafe’s parents took him to a local church for conversion therapy, a place to “pray the gay away.” He was made to sit in prayer for four days, asking God to rid him of his attraction to other boys. He fasted while the staff lit candles around him and anointed him with holy water. A minister made cuts on his stomach and rubbed them with a painful concoction. Eager for relief, Edafe pretended to be moved by the spirit and told his family he had been cured.

In the years that followed, Edafe poured himself into his studies. Education, he believed, was the only thing that could take him far away from his town in Southern Nigeria and allow him to one day be himself. He became the first in his family to attend university, earning a degree in food science, and was determined to work on expanding the shelf life of common household staples to combat food insecurity in his community.

After graduation, Edafe moved to Abuja, the cosmopolitan capital of Nigeria, and found freedom in the city’s vibrant gay scene. “In Abuja, I found myself,” he recalls. “It’s the gay mecca of West Africa. Kiss and don’t tell.” For the first time he had a queer community. Edafe quickly befriended men who had come from other regions of Nigeria — even other countries — to find some degree of freedom and safety. A salon owner named Bobby, who acted as a sort of “queen mother” for recent transplants, took Edafe under his wing and gave him a place to stay when he first landed. He danced the night away at underground balls, held in the homes of wealthy men, and marveled at the drag queens who performed.

When he woke up in a clinic the next morning, bruised and in terrible pain, Edafe decided it was no longer safe to remain in Nigeria.

But the joy of this affirmation was quickly overshadowed. In 2014, Nigerian President Goodluck Jonathan signed into law a sweeping anti-gay bill called the “Same-Sex Marriage Prohibition Act,” which criminalized same-sex relationships and imposed penalties of up to 14 years in prison. Underground parties stopped because of fears of police raids. Angry mobs harassed and beat up queer people in the streets. A once thriving community suddenly went into hiding.

The law against same-sex marriage had other chilling effects. It restricted the work of organizations that provided services to the gay community, including HIV prevention programs for men who have sex with men. Many gay men became fearful of seeking HIV prevention resources, or treatment for suspected infections.

Edafe noticed the shift among his friend group right away. It started when he learned that Bobby had died suddenly. Rumors swirled that the cause of his death was complications of HIV. Soon, scores of his friends had also contracted the virus, and by Edafe’s count more than half of them eventually died of the disease. “People were dying left, right and center,” he remembers. Heartbroken and determined to help his community, Edafe left his job and started working for a health clinic that discreetly offered resources and support to gay men.

The work put a target on Edafe’s back. In 2016, he received an award at the World AIDS Conference in South Africa. Soon after he returned from the trip, a mob stormed his home in Abuja, breaking down his door and dragging him outside, naked. The men beat Edafe, shouting that they would kill him for being gay. They tied bells around his waist and paraded him through the streets. Edafe blacked out from the pain. He still carries a scar on his forehead from the attack.

When he woke up in a clinic the next morning, bruised and in terrible pain, Edafe decided it was no longer safe to remain in Nigeria. He boarded a flight to the United Arab Emirates, and while there planned his next move. An opportunity to escape came in the form of a conference invitation. The LGBTQ+ Victory Institute, an American nonprofit that holds leadership trainings, had invited him to their annual gathering in Washington. This, Edafe thought, could be a way to get a visa for the United States and, once there, apply for asylum.

He flew to New York months before the actual conference was supposed to take place. Upon landing at JFK, Edafe nervously told the customs officer he had come for a vacation. Unconvinced, the officer sent him for secondary inspection. He was questioned further, and informed that he’d be sent back to Nigeria and banned from entering the U.S. for five to 10 years. Desperate to avoid this fate, Edafe said he couldn’t return — that he would be killed for being gay.

Knowing very little about the asylum process in the United States, Edafe never expected what came next. At the airport, he was handcuffed, taken into custody, and transferred to a prison-like detention center. “I thought that America was different,” Edafe says, recounting the experience. “I thought it was going to be like, I’ll be gay, live my life.” Whatever hopes he may have had for relief upon reaching the United States were quickly shattered as he was processed and shown his cell.

Edafe ended up spending five-and-a-half long months at the Elizabeth Detention Center in New Jersey, a facility run by a private prison corporation. Deemed a “flight risk” by the government, he was denied parole while he pleaded his case to the courts. He spent his days trying to reach lawyers, LGBT rights organizations, media outlets — anyone who could help him with the process. He faced harassment from the other detainees once they learned he was gay. Just outside the facility was Newark Airport. From the roof of the volleyball court Edafe could see planes passing by, reminders, he says, of the freedom of the outside world.

Edafe felt a calling in this work with fellow migrants, and decided to pursue it as a new career.

Eventually, Edafe found his way to a group called Immigration Equality, which represents LGBTQ asylum seekers. Two volunteer lawyers from a Manhattan firm agreed to represent him. On the day of his court hearing, Edafe testified about the hostility he faced for being gay in Nigeria. Holding back tears, he described in painful detail the night the mob attacked him. To Edafe's immense relief, the immigration judge overseeing the case granted him asylum, giving him the right to live and work in the United States.

Though he was finally free, life immediately after detention brought its own set of challenges. A friend hosted Edafe in her living room for three months while he searched for work, struggling to find a job that aligned with his qualifications back home. The next year brought a quick succession of roles. He started out as a street canvasser for an LGBTQ rights organization, then spent several months putting his food science degree to work developing recipes for “Eat Offbeat,” a refugee-run kitchen. After that he found a job working for an AIDS foundation in New Jersey, hoping to re-enter the field he had left in Nigeria.

Two years after winning the prize, Edafe founded a new organization called Refuge America, which he still runs.

While building his new life in America, Edafe kept coming back to the experience of his arrival: the sense of betrayal he felt when he sought safety from violence only to find himself locked up; the isolation of life in detention; the uncertainty of the immediate months after release. He started volunteering for a group called First Friends, which had helped him during and after his detention. Edafe felt a calling in this work with fellow migrants, and decided to pursue it as a new career.

As it turned out, a shelter in Harlem was looking for a new director, and Edafe was encouraged to apply by a fellow First Friends board member. RDJ Refugee Shelter, housed in a church and named after homelessness advocate Robert Daniel Jones, was the only facility in the city that exclusively served this population. The residents there reminded Edafe of his own journey, fleeing persecution and violence in their home countries only to be met with a host of new struggles in the United States.

Edafe turned the shelter from a winter shelter open for three months a year, into one for LGBTQ asylum seekers and refugees experiencing homelessness. He spent three years running the shelter, managing its operations, coordinating volunteers, fundraising, applying for grants, and advocating for the asylum seekers who stayed there. On nights when there weren’t enough volunteers on hand, he would cover the evening shift, making food overnight and exchanging stories with the residents.

Early in his tenure, he was reunited with another former detainee from the Elizabeth Detention Center, a transgender woman from Honduras named Jenny who needed a place to stay after her release. Jenny became a client of the center, and though she finally had a place to rest her head, she still faced threats on the streets of New York as an openly trans woman. One day, Edafe had to rush to a local police precinct to help her after she was attacked near the shelter. It was moments like these when he felt acutely the threats that queer refugees face — as well as the limitations of his role. He could provide a warm bed and a welcoming community, but to help his fellow LGBTQ migrants find a deeper sense of security, Edafe felt drawn to advocacy on a larger scale.

With many of newly arrived refugees, Edafe sees his own journey reflected back at him.

In 2020, Edafe was among the first cohort of David Prize recipients for his work with RDJ Refugee Shelter and his vision to make New York City a more welcoming place for queer migrants and asylum seekers. The award gave him some much-needed breathing space, time, and funding to chart out the next phase of his career. It also helped him understand the value of sharing his story, as well as the stories of those like him. He learned that many people are moved to help when they hear about the unique struggles that LGBTQ refugees face. They just need opportunities and resources to make it happen.

“The David Prize gave me that room to be myself, to explore what I want to do with my work with no strings attached,” he says of the experience. “That is really helpful, especially for someone who does not feel like they deserve things sometimes.”

Edafe found other ways to share his story and channel his creativity. In 2022, Simon and Schuster published his memoir Asylum, which recounts his journey and insights as a gay refugee. He also wrote a one-man play about his experience, called “Do Not Tell Them I am a Prince,” which toured New York State in support of legislation to end ICE detention.

“I think we all have the same story, but just different patterns. People are resilient.”

Two years after winning the Prize, Edafe founded a new organization called Refuge America, which he still runs. The work of the organization centers on advocacy and practical support for LGBTQ asylum seekers and refugees. Through his work at RDJ Refugee Shelter and his own experience on arriving in the U.S., Edafe saw firsthand the ways in which established support systems for refugees often fail to consider the unique circumstances of those in the queer community. One of his main initiatives at Refuge America is training resettlement agencies, such as the International Rescue Committee, to better serve LGBTQ individuals under their care.

Through Refuge America, Edafe is recruiting and training volunteers to sponsor LGBTQ refugees, the first of whom have already arrived. In the spring of 2024, he traveled to Chicago to meet a new arrival from Uganda, along with the group of sponsors he had arranged for them through his organization. At O’Hare airport, he watched with pride as everyone got to know one another. “The group quickly realized that they are not there to lead the person,” he recalled of the arrival. “They are there to support the person in their journey.”

The LGBTQ refugees he meets have experienced a great deal of suffering and trauma, to be sure, but they are determined to build a better future for themselves. With many of these newly arrived refugees, Edafe sees his own journey reflected back at him. “I think we all have the same story, but just different patterns. People are resilient. They’re like: ‘I'm going to make it, I’m going to make it’.”

“Yeah you are going to make it,” he responds to them. “Your time will come.”

As for Edafe, the time has come to draw on his experience as an advocate in an entirely new endeavor: seeking political office. In 2024, he announced his bid for New York City Council in Upper Manhattan’s District 7, running on issues of affordable housing, access to healthcare, and public safety. In his adopted home, Edafe is continuing to find new ways to inspire, organize, and make lasting change.