2024

Gregory

Purnell

The first time Greg Purnell picked up an electric razor, he was 12 years old. Except his was not some adolescent experiment in shaving. It was 1986, and his friend Warren had plans to take a girl to see Spike Lee’s She’s Gotta Have It. Warren was hoping for off-screen romance too, but a grown-out haircut was working against him. He had spent most of his cash that summer on a pair of Air Jordans. It was either movie tickets or a haircut, and the movie tickets were non-negotiable. “Desperate times called for desperate measures,” Greg remembers.

Warren went to get his father’s clippers, handed them to Greg, and told him to just do the best he could. Greg had never cut so much as a strand of hair, but the clippers came alive in his hands. He could see the design he wanted to execute. Draping a floral print sheet over Warren’s shoulders, Greg proceeded to deliver a clean skin fade with a smooth, half-moon part. When he finished, Warren applauded. Greg wasn’t old enough to see a PG-13 movie… but suddenly, he was a barber.

Word traveled fast around the neighborhood, and Greg became known as “The Five Dollar Man.” Determined to be prepared for would-be clients, he started to keep clippers in his book bag. He picked up customers at pick-up basketball games. Repeat customers brought friends to see him. Soon, he was running extension cords into the halls of housing project complexes, giving impromptu trims to men twice his age.

Now 50, Greg has been cutting hair for well over three decades. Circumstances shift, but some things never change. Today, the feeling of giving someone a fresh cut remains supremely gratifying, and Greg has seen how people transform in his chair. That kind of metamorphosis has driven him to embrace a simple conviction: that the humble haircut has the profound power to make a difference.

Greg was born and raised in Brownsville, Brooklyn. A lifelong New Yorker, he experienced the crime-riddled 1970s and 1980s up close. He has vivid childhood memories of seeing crack cocaine vials littering neighborhood park grounds, feet or inches from where kids jumped rope. Both of his parents and whole swaths of his extended family were touched by the crack epidemic. He lived in and out of shelters.

For all their struggles, the people closest to him were insistent that Greg stay out of trouble. His mother, who would later get clean herself, was clear with her son: He would have to make different choices. “She planted a moral compass in me,” Greg says. “She always told me, ‘Keep God first.’” His maternal grandfather set an example, too. Olin Purnell moved to New York from North Carolina and couldn’t read or write, but managed to get a job. He was “old-school, traditional,” Greg says. He woke up early. He dressed well. He showed Greg that real men cared for and cared about the people they loved. Later, Greg learned that his maternal ancestors were Irish sheep shearers who had moved to North Carolina and applied their skills to human hair. “It’s in the blood,” as Greg puts it, smiling. No wonder those early jobs felt like a homecoming.

Greg soon realized that cutting hair could be more than a vocation. “It gave me a way out,” he says. Walking around Brownsville, he was always on the lookout for the kids who needed a pick-me-up. “I couldn’t let a little kid walk by if he needed a haircut,” Greg says. “If he didn’t have money, and he was looking sad, I had to be like, ‘Sit down.’”

For Black men especially, places where it’s okay to voice insecurities or talk about fear are few and far between.

Greg found barbering at the right time. Consciously or not, he’d been casting about for examples of what manhood could look like. Being a barber gave him permission to operate with a softness and attention that he might not otherwise have been able to claim. “You think of a man touching another man’s face in a society that doesn’t allow us to be vulnerable? In any other situation, that’s a no-no,” Greg says. “But in these moments, in a barbershop, it’s a dynamic that transcends.”

Greg was 15 when he was hired for his first real job. The gig was out of a barbershop owned by a relative of actor and comedian Martin Lawrence. Greg was technically too young to work there; he was still a high school student without a formal license, but his designs were unimpeachable. After a few years, he tried college because his mother wanted him to go, but he could never totally commit. “I feel like when someone wants to learn something, they’ll learn it,” he says. “I didn’t want to go to school and waste more years trying to figure it out when I had this thing that I love and enjoy.” Instead, he indulged his curiosity with customers, asking them about their careers and their travels.

He opened his own space in 2008. That first shop was in Sunnyside, Queens, but his soul was still in Brooklyn, as was his home. So he closed up shop and moved his operations into his garden-level apartment. Far from minding, his landlord started to come to Greg for haircuts. And within a matter of months, it became clear to him that a more under-the-radar operation was a good fit. He hasn’t had a formal storefront since and haircuts are always by appointment. The policy isn’t meant to be exclusive, and it’s not about money or clout. Rather, it's designed to ensure that his clients know he's invested in their safety, preserving what makes his space so special. “I feel your vibe is your tribe,” Greg says.

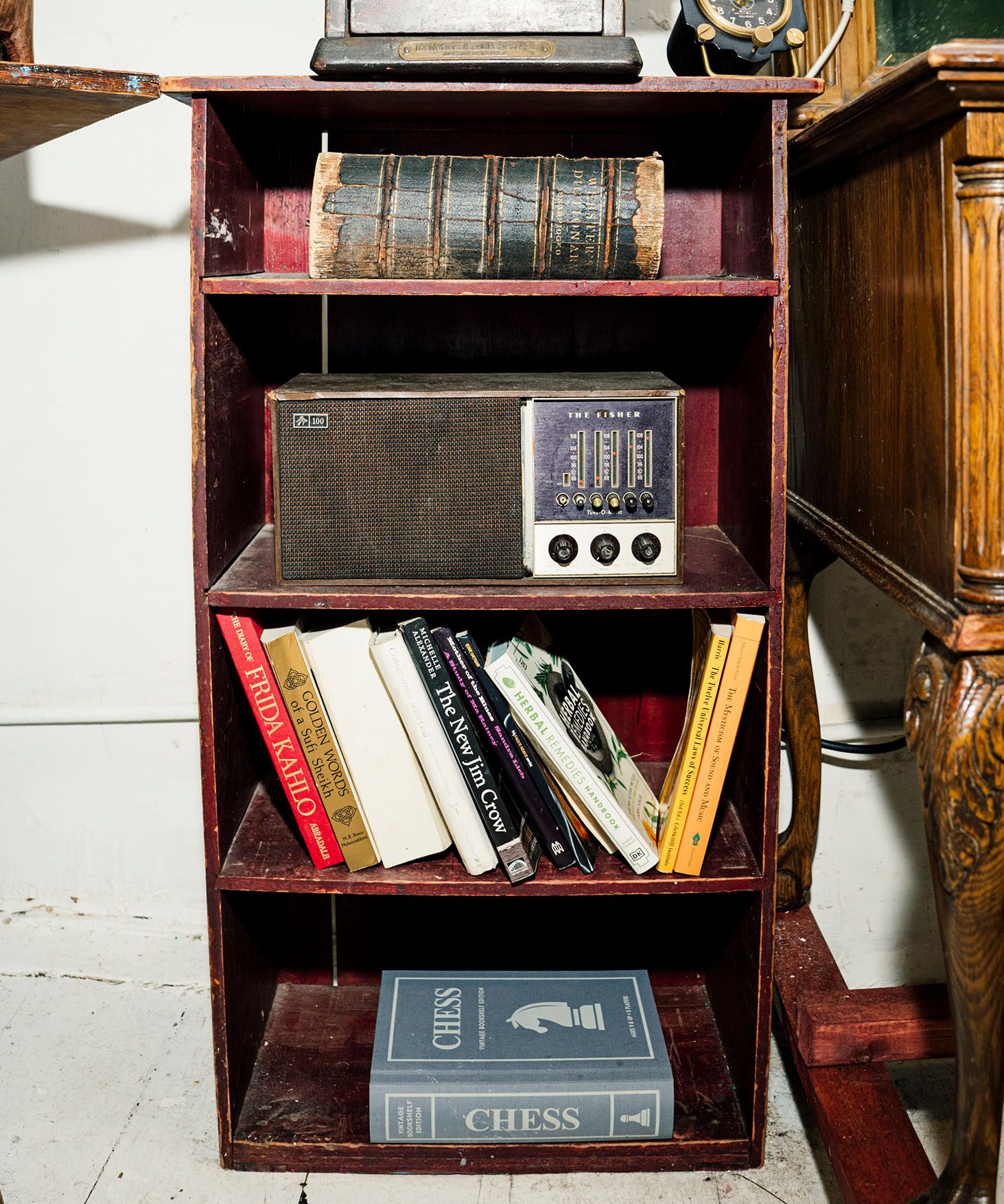

For Black men especially, places where it’s okay to voice insecurities or talk about fear are few and far between. Greg has filled his de-facto studio with plants. He has a sound bowl that he likes to break out when he feels the energy needs to shift. In his very presence, he radiates warmth and openness. The atmosphere in that room is his most intangible treasure, and he has to be intentional about keeping it that way. Maybe that’s why the last time Greg set a price, he was the 12-year-old “Five Dollar Man.”

“I have my register back here, and I don’t need to touch it,” he says. “People put whatever they feel or whatever they can in there. Some people put less, some people put more.” Somehow, it evens out.

Over the last two years, Greg’s work has gotten more consistent and more purposeful.

Since friendship is what first pulled Greg into this kind of work, perhaps it’s no surprise that community engagement has always been part of his calling. His first foray was a program he pioneered called Cuts for Grades. When he was scarcely out of school himself, he started offering free haircuts to students who maintained a certain GPA during the school year. Still, it was after Greg’s mother died in 2011 that he really began to reflect on what a person in his position could offer to others. The years after she passed were particularly hard. He wanted to do something with that pain. And he hoped too that his daughter, Sage, who is 19 now and an artist herself, might feel proud of his work.

More recently, he’s been able to feel his mother’s presence in a way he couldn’t in the immediate aftermath of her death. “I hear her,” Greg says. She urges him on. That encouragement is part of what inspired him to formalize his efforts to reach out and give back to the community. Five years ago, he started volunteering his services in homeless shelters. He now works with the LGBTQIA+ community too, helping them to express the deepest and truest parts of themselves through their hair. Over the last two years, that work has gotten more consistent and more purposeful. It has felt like a way to honor his mother, who lived in shelters more than once. And it’s allowed him to offer something that he is in a unique position to provide.

“My most valuable tool is my ability to empathize because that is what helps me give them the style of haircut that suits them. I get to explore their lifestyle.”

“Just from understanding that perspective, I know the little things that would’ve helped along the way,” Greg says. “Waking up, going to school, looking decent, it makes a difference. And in our community, in Black and Brown communities, hair is a staple. You can go get a suit from the Salvation Army. You can get food from a soup kitchen. You could even get a Metrocard for a job, but if you don’t have a decent, presentable haircut, you’re probably not going to feel as confident as you should, and it’s going to interfere with how you’re engaging.” Thinking of his clients who are experiencing housing instability he adds, “Sometimes, a haircut can just change their whole sense of themselves.”

The sacred space that he establishes is a reciprocal one. “When we’re in front of a mirror as I’m cutting your hair, it’s like we’re reflecting one another,” Greg continues. “So we’re growing and experiencing together. I feel every time someone sits in my chair, I’m traveling without moving. My most valuable tool is my ability to empathize because that is what helps me give them the style of haircut that suits them. I get to explore their lifestyle. And in that process, things come to the surface.”

Lately, he’s been thinking about what it might look like to scale up, and he’s launched an organization called Look Good, Feel Good to partner with shelters in New York so that a network of trained barbers can extend this movement’s reach, at no cost to the people who need them. Technically, Look Good, Feel Good is in the business of hair. But Greg knows — as does everyone who’s sat in his chair — that barbers are therapists, social workers, life coaches, artists, spiritual advisors, and mentors. His team will do so much more than shape and style.

Eventually, he hopes to buy a building and use hair as a foundation and a metaphor for self-expression—home to writing workshops, movie screenings, and open-mic nights.

Greg’s oldest clients have been seeing him for 35 years. There are kids whose hair he has cut since birth. He’s watched them grow up and head off to college. “It’s a blessing to me,” he says, “because I don’t have much family.” Besides his daughter and some scattered cousins, he’s never had a lot of kin. His clients have filled that void.

He sees his space as their space. Once a month, he invites kids in for free haircuts. He likes the idea of someone throwing a baby shower there. People will be able to host memorial services for loved ones. He’s in an expansion mode now, and he’s dreaming big. He’s ordered portable barber stations so that his network of barbers and beauticians can be more mobile. He’d like to develop a voucher system, too, so that shelter residents can come into barbershops and salons rather than have to wait for providers to come to them. “This place would be the headquarters for that,” he says, gesturing around the light-filled space. Eventually, he hopes to buy the building and use hair as a foundation and a metaphor for self-expression — home to writing workshops, movie screenings, and open-mic nights. He asks himself: How can this place be a three-dimensional refuge that pushes back against digitization and alienation and mass production? How can it keep feeling like home, not just for him, but for the people who come through its doors?

“I met that mildlife era,” he says now. He felt low, but responded to that darkness with a sense of determination.

Of course, there have been moments of doubt along the way. During the pandemic, when barber shops and salons were forced to close, Greg seriously questioned the instability he’d chosen for himself. “I met that midlife era,” he says now. He felt low, but responded to that darkness with a sense of determination. He made space for the “voices of his ancestors,” who were guiding him down a different trajectory. “I know they’re all cheering me on,” he says. “They’re like, ‘You may not be winning in the material realm, but in the spiritual realm, you’re shining. Keep going. We got you.’”